Feathered Hope

By Fr. Bartholomew Calvano, O.P.

“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

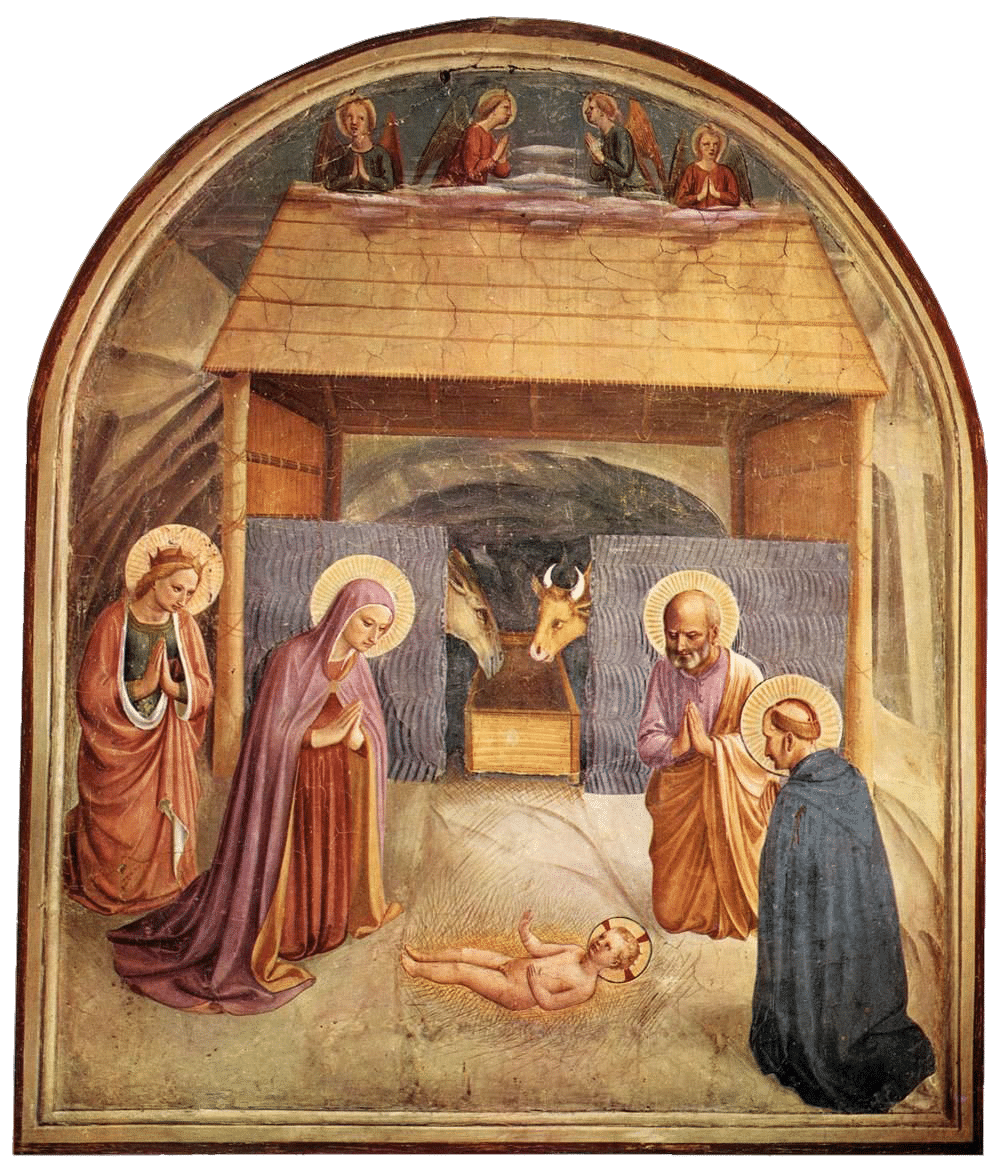

I cannot help but hear these lines of Emily Dickinson ringing whenever I think about hope. A bird is an apt image for this virtue since in a particular way the Holy Spirit, who once manifested in the form of a dove, is the Comforter. Likewise, the blasphemy against the Holy Spirit that is the unforgivable sin is despair, the opposite of hope. The tune without words hearkens back to the inexpressible groanings with which the Holy Spirit intercedes for us.

It is an axiom of Thomistic thought that grace elevates nature. The supernatural virtue elevates a natural habit of hope. The object, the goal of hope, is a possible, future, difficult to obtain good. When it is a supernatural virtue, that good is God himself. The astounding thing is that with this virtue, God himself becomes a possible good. We can actually receive God. This is a real hope we can have. It is still a difficult good that we cannot accomplish on our own. That is why in order for us to hope for God, the virtue also causes us to hope in all of the helps that God promises. These helps are the many graces he pours out on us, especially in the sacraments, as well as the prayers of all the saints of the church for us.

The image of the final two stanzas of Dickinson’s poem is of a bird continuing to sing in the midst of a storm. The birdsong brings warmth to those who are being overwhelmed by the tempests of life. This complements well the image in Hebrews of hope as the anchor of the soul. This anchor keeps us from drifting from the Kingdom of God and draws us up to heaven. The anchor is Jesus Christ, the head of the body. The Ascension, that Jesus, our head, is seated at the right hand of the Father, is the greatest cause of our hope. If Christ is our head and we are his body, we can expect to follow where our head has gone before. Jesus is the anchor that keeps us from drifting in the storm. On that account, no matter how hard the winds blow and the waves crash, we will not be driven from Christ.

Those winds and waves that roil our frail ship about tempt us to despair or presumption, the two opposing vices to the virtue of hope. Despair is by far the most common and it is a sin of defect. We fail to hope in God enough when we despair. When we despair, our hope fails to believe in our personal salvation. The person who is despairing so often believes both the universal truth that “God can forgive any sin,” and the particular truth that “I have sinned,” but cannot complete the particular syllogism to conclude that “God can forgive my sin.” As a result the person who despairs cannot ask for forgiveness. The virtue of hope disposes us to accept God’s mercy for ourselves.

Presumption is less common because it stems from an excessive trust in God’s mercy. In one sense, there is no way that we can trust too much in God’s mercy, but we can trust in it the wrong way. We do this when we trust in God’s mercy and deny his justice. Despair tips the scales too much in favor of God’s justice but presumption tips them too much in favor of God’s mercy. Presumption is when, before we sin, we trust in God’s mercy and so reject his justice. This is different than trusting in God’s mercy when we are struggling with habitual sins of weakness and fall frequently. These are sins of malice and it is far harder to be contrite and ask God’s forgiveness when you have chosen so deliberately beforehand. The person who is presumptuous does not feel a need to ask for forgiveness.

God is totally simple. There are no parts or divisions in God. That means that God’s mercy and justice are not two different things. Mercy and justice are one in God. The virtue of hope helps us to trust in who God really is and not false understandings of mercy and justice. That trust allows us to confidently turn to God in every situation. We recognize our need for him and his love for us. Therefore, we have hope.