By Fr. Pier Giorgio Dengler, O.P.

One reads about the marvelous life of St. Thomas—about the many travels on foot from central Italy to the monastic fortress of Monte Cassino, the metropolis of Paris, the battle of Cologne Germany, and all sorts of places in between; about the intense study and teaching (even dictating different works to multiple scribes at one time); about his devotion to the person of Jesus Christ, especially to His Presence in the Eucharist; and about his silent contemplation, so much so that his peers at one point dubbed him “the Dumb Ox.” I got to experience a taste of all this when I spent three intense days with him this past December. Or with a substantial part of him, at least.

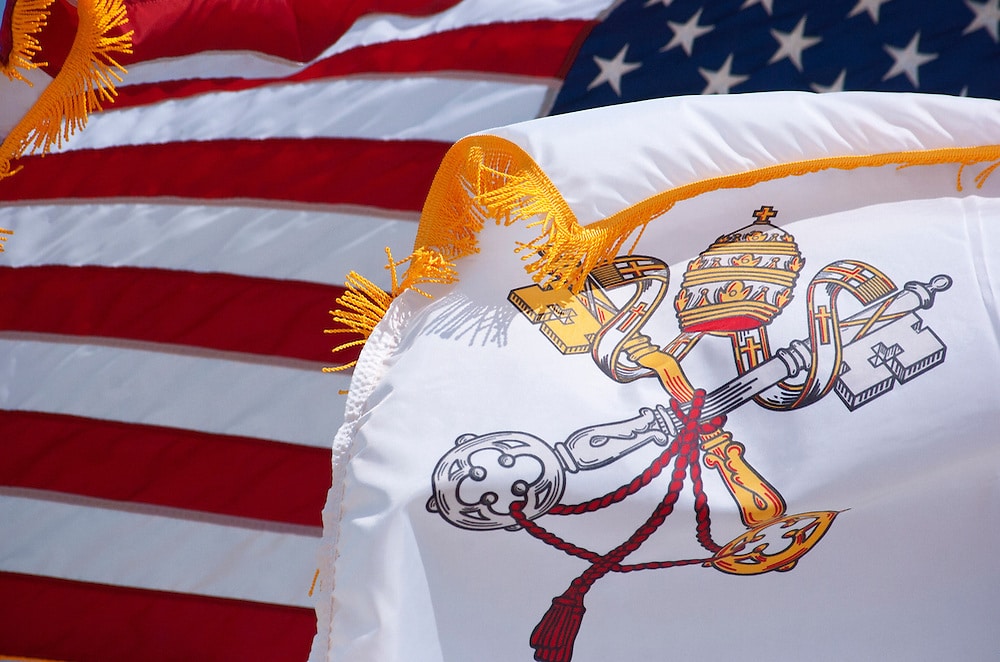

From late November until mid-December, the skull of St. Thomas Aquinas came to America as part of the celebration of major anniversaries of this saintly Dominican friar and Doctor of the Church. In the 800 years since his birth, it was St. Thomas’ first time on the American continent and for security reasons, as much as for hospitality to our brother, he was always to be in the presence of a Dominican on his visit here. Early in the morning of December 11, a friar from St. Louis Bertrand and I carefully hefted a crate with our brother’s noggin into the back of my car. I’d then take him to the countryside of Kentucky, once the American frontier and the birthplace of the US Dominican provinces.

St. Thomas was a hit everywhere he went. A few hundred school children from St. James Elementary School in Elizabethtown and St. Dominic’s in Springfield visited the relic. Reactions of the students ranged from a wide-eyed, “that’s spooky,” to a hand-drawn double-thumbs-up smiley-face emoji. Others related that they experienced a remarkable sense of peace in the presence of this saint. One student wrote, “Venerating the relic was an incredible experience, I really was able to slip into the tranquility of the moment and . . .reflect deeply.” This sense of calm and order would likely have warmed the heart of St. Thomas, whose scholastic mind saw order as evidence of God’s guidance of creation, and whose contemplative soul rejoiced to rest in the Lord.

The Dominican sisters of St. Cecilia, who teach at St. James in Elizabethtown, were moved to pray, chant, and also casually congregate around their revered “older brother.” Catholics from all around the region and from other states—as far as Georgia and Arkansas—arrived, kneeling silently and touching rosaries, medals, scapulars, and holy cards to the beautiful reliquary. One especially informed and talented group quietly ascended to the choir loft and offered an impromptu choral concert of St. Thomas’ Eucharistic hymns, including Adoro te Devote and Pange Lingua.

What those who venerated the relics of St. Thomas encountered was the wonder of holiness lived in human flesh and blood. Saints are living treasures of man fully alive with the glory and love of God. Their relics—bone, flesh, blood, or other memento of the actual saint— connect us with the personal reality of that love. They are a human anchor here on earth, unforgotten by and related to the soul that even now beholds the radiance of the Beatific Vision of God himself in heaven. To be in the presence of a relic—especially one so significant—draws us closer up and farther into the thrill of the salvation won for us by Jesus Christ. Relics are sensible and irrefutable proof that holiness is possible and salvation is real.

The saints know first-hand the fulfillment of Jesus’ words to the apostles in chapter 14 of John’s Gospel: “I go and prepare a place for you, [and] I will come again and will take you to myself, so that where I am, there you may be also. You know the way to the place where I am going.” Relics are proof that real people came to know and walk in Jesus’ Way. Miracles associated with relics of the saints prove that God loves to act through human intercessors—not just in incidents recorded in the Bible, but today! In fact, during the veneration of the relic of St. Thomas at St. Rose, I shared a story of a local priest, Msgr. Joseph Gettelfinger, who, in the late 1950s, was miraculously cured of cancer thanks to a relic of St. Martin de Porres—another Dominican saint. We still need miracles, healings, wisdom, and grace today and the saints continue to be instruments of those divine graces.

Over the nearly forty hours of St. Thomas’ stay with me in central Kentucky, I found myself with the opportunity to preach about the life and legacy and faith of St. Thomas. Of course there’s his scholarship and marvelously clear explanations of Catholic teaching, but I also introduced people to stories of his devotion—such as his resting his head on the tabernacle in a wordless plea for help to receive, comprehend, and hand on the mystery of the Eucharist. Or his legendarily bold defense of his chastity and purity when held prisoner in his family’s own castle. Our world still struggles to comprehend God (in part because it has ceased to take seriously St. Thomas’ Catholic faith, let alone read the Summa Theologiae), and the rampant abandonment to lust destroys the purity of countless lives today. In our day and age, St. Thomas—his way of life, his priestly vocation, his sound theological teaching, and his piety—are sorely needed. No doubt God’s grace set in motion the tour of his major relic to unleash a champion of holiness into the fray.

All these ideas seeped into my head as I embarked on the next phase of my adventure with St. Thomas—a 12-hour, overnight drive to bring the relic from St. Rose in Kentucky to St. Vincent Ferrer in New York City. The night’s voyage with fellow friar, Fr. Raymond Lagrange, O.P., gave me the chance to converse about the experience as well as long stretches of contemplative silence to let it all sink in.

We chose the desperate drive because Fr. Raymond wanted to allow the high-schoolers of St. Vincent Ferrer Academy (yet another school run by Dominican sisters), where he serves as chaplain, to be able to welcome St. Thomas into their school for the second half of their school day the next day.

Sped along by empty roads with a focus on a simple mission, we made such good time in the dark, that we were able to divert to a nearby monastery of cloistered Dominican nuns shortly after dawn. As their daily Mass ended I gassed up the car, and Fr. Raymond delightfully sprung the news to the nuns that a fellow Dominican they might know just happened to drop by. These saintly women took the news in perfect stride—delighted, but not at all surprised. “Oh,good, I had prayed for this,” the portress said with the natural calm born of a contemplative’s unshakeable faith. While the relic was carried into their chapel for an hour’s visit, Fr. Raymond and I were treated to a hearty breakfast in their visitors’ wing. There we chatted with the parents of one of the most recently professed nuns, who hailed from Australia. Their daughter being convert, our coffee-mates were experiencing faith-fueled adventure of their own, visiting a monastery within the greater New York metropolitan area, and hosting a medieval saint and his two younger brothers from the current century. Part evangelization, part cultural exchange, and part caffeine, we departed for our final destination with full stomachs and satisfied Dominican hearts.

As we reached the far side of Jersey City, the Manhattan skyline rose before us, clawing upward like a confused steel-and-cement cacophony of Babel, still vainly trying to project man’s own ego into the heights of immortality. Our route brought us humbly downward instead. Crossing the Hudson River dry-shod by means of the Holland Tunnel, I reflected on a symbolic closeness between the golden square reliquary of St. Thomas’ skull, and the Ark of the Covenant (even more so if your last visual image of it was encased in a wooden crate and wheeled through a warehouse of government secrets from the movie Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark) Indeed, as we surfaced in New York City, our progress ground into gridlock and with a glazed numbness, we became an identity-less cog in the wheels of the uncaring juggernaut of downtown traffic.

Undaunted, Fr. Raymond turned the potential disappointment of delay into an occasion to heighten anticipation among the high-schoolers. He snapped pictures of landmarks as we headed northward—Broadway, Madison Square Garden, Grand Central Terminal—and he shared our progress step-by-agonizing-step as we fought relentlessly, ever closer, to the Upper East Side. Rolling along the viaduct through the Helmsley building and breaking out onto Park Avenue, our electronically-informed followers grew more expectant, and as I pulled up alongside the school’s back door on East 65th Street, a teacher swung open the portal, and the local pastor helped Fr. Raymond bear the precious cargo up to the second-floor chapel, the stairway lined with cheering students.

It’s especially appropriate that my travels with St. Thomas’ major relic began and ended with the “Common Doctor” being visited and venerated by children (and their teachers) at Catholic schools. After all, St. Thomas is the patron of Catholic schools and of students in general. As the patron of the Angelic Warfare Confraternity, he also leads the charge for purity, desperately sought in this world where lust, pornography, and sexual objectification are common-place among citizens of this digital age, no matter what their age or background.

My journey with St. Thomas paralleled the history of our province—from its original start in Springfield, Kentucky to its current headquarters in New York City. The major relics of St.Thomas afforded me many opportunities to preach—in church as well as over coffee—as well as to watch, listen, learn, and contemplate. His presence here not only edified me with my own personal opportunity to venerate his relics, but walked me through an exitus-reditus leading me there and back again, but changed, deeply impressed with the effect of Dominican holiness on the world and my fellow pilgrims in it. From the bluegrass to the Big Apple and back, I witnessed men and women of all ages looking with wonder, with hope, and in faith to a giant of scholarship, a champion of piety, and a brother in the order of St. Dominic. His life, and the relics left behind, teach us how to follow Jesus who is “all in all.”

✠

Photos by Jeffrey Bruno and John Osterhoudt